Torres-Hugon Vincent,

Gesture historian living history anthropologist,

Guide-lecturer with cultural tour operator CLIO.

Thanks to Floriant Razafi for the translation

This article is a digest of the first part of our 2nd year of master [1] Vincent TORRES, under the direction of Philippe JOCKEY (2015), “L’apport de l’expérimentation sur l’histoire du geste martial, cas d’étude appliquée : le déplacement au sein de la phalange dite hoplitique, approche expérimentale. ” (The contribution of experimentation on the history of the martial gesture, applied case study: movement within the so-called hoplitic phalanx, experimental approach) Dissertation 2 of history at the University of Aix-Marseille thesis and the presentation of the armament of the book “Hoplite, le premier guerrier de l’histoire” [2] Vincent TORRES, (2018), “Hoplite, le premier guerrier de l’histoire”(Hoplite, history’s first warrior), éditions Heimdal, Bayeux (Hoplite, History’s first warrior) .

The armament of the Greek hoplite

Etymologically the term hoplite refers to the idea of the wearer of the heavy infantryman warrior panoply from the 8th BC to the 4th BC century. Therefore, it is only natural to better understand this fighter to clearly describe the equipment composing this panoply, because it is the latter which influences on his martial possibility on the battlefield. The purpose of this article is not to make a deep study of each piece of equipment and its use, this will be with no doubt the goal of others works, but to give a clear and concise description of it.

The shield

Let’s begin with the most important part of the entire hoplite equipment, the famous round and hollow shield “Aspis koilè” [3] The round shield, called hoplon, is named as such by Thucydides alone.. This shield is made out of wood as it is shown by the few textual mention regarding this subject as well as the scarce archaeological sources that reached us, such as the Vatican shield. Circular (an average diameter of 90cm but this was probably varying depending on the size of the bearer), the centre was curved toward the exterior, so that the hoplite can place his shoulder inside this space thus formed in order to better support its weight. To complete this protection, the bulge of the shield has a rim called the Itys that goes around it. To hold it, the hoplite passes his left forearm in the central hook of the shield, the “Porpax” and will grasp a handle called “Antilabe” located on one of the edges of the bulge. This double hook has led to extensive coverage in the works of modern historians. According to them it is this specificity which allowed the hoplite to better manoeuvre its shield and to better support its weight [4] On this shield, see Pierre DUCREY, (1985), Guerre et guerriers dans la Grèce antique. (“Warfare in ancient Greece”) Fribourg, Office du livre, 1985.. The invention of this system seems so important that Herodotus does not forget to mention its origins. This information shows that, for a Greek, this technical feature was of primary importance [5] Herodotus, Histories, Book I / 171: “…the first [he speaks of the Carians], they equipped the shields with straps [Porpax] to pass the arm through”.. Indeed, the latter force oneself to face the opponent head-on and makes it easier for the hoplite to wear the “Aspis Koilé”.

The Somatophylaques association has reconstituted them and their weights vary between 4 and 5 kilos per shield [6] This weight is slightly lower than the 7 kilos advanced on page 341 in the study by Walter DONLAN, James THOMPSON, (1976), The charge at Marathon: Herodotus 6.112, The classical Journal vol.71n No.4 PP.339-343, perhaps because we have not added a bronze coating. Indeed, these are never very thick and do not offer any real resistance to a spear hit. They are rather a decorative element of the hoplitic equipment allowing in particular to show the richness and thus the power of its owner. This can be explained by the absence of bronze covering which was certainly common but not imperative and majority within the hoplitic equipment.

The offensive weapons:

It should now be remembered that the hoplite is reputed in antiquity to be a formidable lancer, its main offensive weapon is the “Doru”, a spear ranging in size from 2 to 2.50 meters [7] For all that relates to offensive armament we refer here to the study by J.K. ANDERSON, (1991) “Hoplitic Weapons and Offensive Arms, in Hoplites, the Classical Greek Battle Experience”, V.D. Hanson, p.15-37, London, Routledge. The latter is generally made of ash or dogwood, two species offering good resistance to the often rather thin shafts. The spearhead is in the shape of a willow leaf, usually 20 cm long. It is sometimes equipped with a bronze heel called “Sauroter”, whose weight helps to balance the spear. Although the latter is quite suitable for individual confrontations, it remains above all a weapon that is simple to use and easy to produce to equip citizen armies!

Although the spear is the most important offensive weapon of the hoplite, these warriors may also carry a blade at their side although this is more rarely represented in iconography as well as found in archaeology. There are two types of blades, the first is the “Xiphos”. A straight double-edged blade with a central rib, it is suitable for cutting or thrusting the opponent. The second type of blade is curved inwards and is called “Kopis”, a Greek word with the same roots as the French verb couper (to cut). With only one edge and rather used by horsemen, this weapon is mainly intended for slice attacks. The use of these “swords” in certain confrontations longer than usual is attested by ancient sources and in particular by Herodotus when he wrote about the battle of Thermopylae [8] Herodotus, Histories, Book VII, 224: “Their Spears were soon broken almost all, but with their Swords (in the text, Makhaira, the term for all Greek blades), they continued to massacre the Persians. ».

The defensive protections

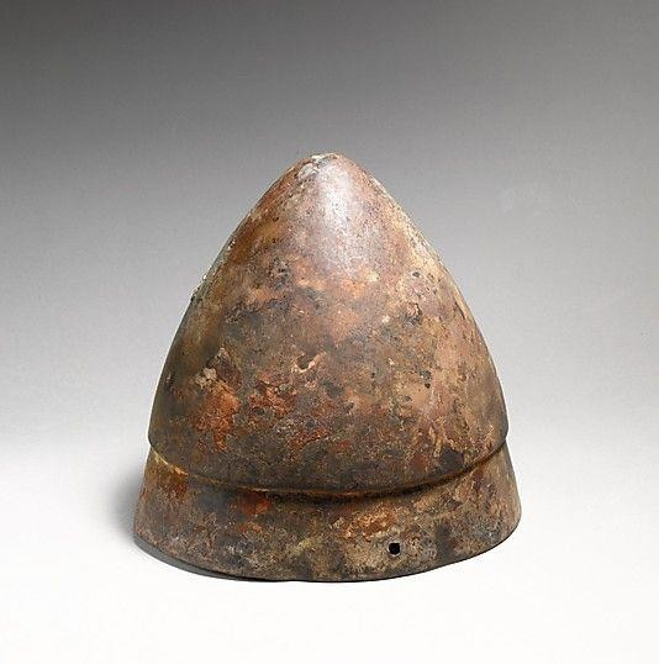

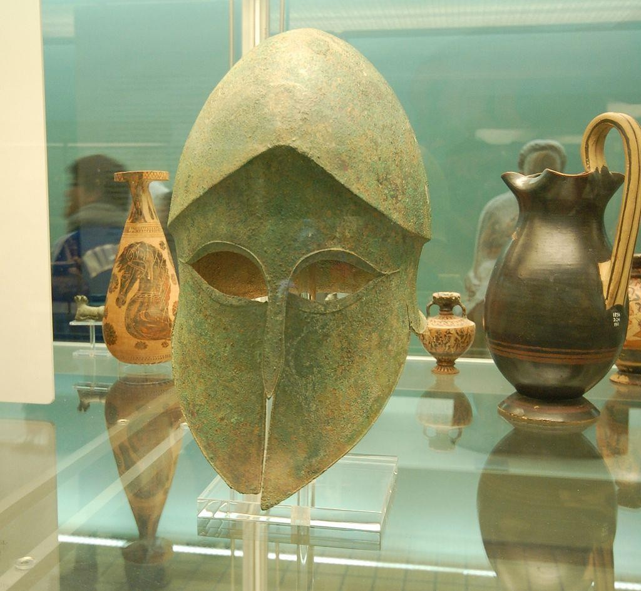

As far as defensive equipment is concerned, the hoplite in most cases wears a bronze “Kranos” helmet [9] On Greek helmets, we refer here to the beginning of Michel FEUGERE’s book (1994): Casques antiques: visages de la guerre de Mycènes à l’Antiquité tardive (Ancient helmets: faces of the War from Mycenae to Late Antiquity), Paris, p.7-22.. This protection was necessary to protect the fighter from the opponent’s downward blows. Usually the helmet is 2 mm thick, but sometimes it can reach 3 to 5 mm depending on the helmet area (especially on the face). The helmet is always worn over a form of padding consisting of a simple wool or linen cap sometimes covered with leather and usually sewn directly to the helmet. Few examples have come down to us today, but fortunately one of them can be found in France in the Mougins Museum of Classical Art. Moreover, many Greek helmets on display in museums have small holes in their edges, attesting to the presence of these padding sewn to the metal. There is a wide range of very different “Kranos” that have evolved over time. However, it is possible to identify several main types. First of all, the most emblematic helmet of the archaic period is obviously the so-called Corinthian model. This helmet protects the whole of the skull but also the face and neck of the wearer but reduces visibility and breathing capacity. However, more open helmets exist at the same period, such as the Chalcidian, Illyrian, or even Boeotian models, each of these helmets opening the field of vision of the fighter a little more and allowing better breathing while preserving the protection of the skull. They have all survived the classical period while becoming more refined. Towards the end of the 5th century a helmet became more and more widespread, the “Pilos”. This helmet only protects the skull, leaving the warrior’s face completely exposed. Yet important armies adopted it en masse, such as the Spartan army. Some historians such as LENDON see it as a provocation of the latter who, in order to prove their courage, refused to hide their faces from their adversaries [10] Jon Edward LENDON, (2009), Soldats et Fantômes : Combattre pendant l’Antiquité, translated from English by Guillaume Villeneuve, Editions Tallandier, collection Antiquité, p.75. Whatever happens, it is important to note that the skull is always protected, regardless of the type of helmet.

To this defensive protection of the hoplite, it is common to add the “Greaves” and the “Thorax”. Admittedly, at the beginning of the hoplitic wars, in this archaic period when only well-to-do farmers paid for the expensive equipment and fought among people from the same milieu, these pieces of equipment were omnipresent. In later periods, however, it is common to see large numbers of low-born hoplites going into battle without these expensive pieces of equipment [11] For all references on the engagement of low-born hoplites equipped at the last moment with the minimum of what makes a hoplite, namely a shield, a spear and if possible a helmet protecting the skull, see Victor Davis HANSON, (1990), Le modèle occidental de la guerre, La bataille d’infanterie dans la Grèce Classique, translated from English by Alain Billault, Les belles lettres, collection Histoire, p.61.Moreover, even some war professionals, such as the mercenary hoplites of Xenophon’s Anabasis(The March of the Ten Thousand), did not all seem to carry such heavy equipment and could go into battle without them.

“all Greeks wore brazen (a kind of copper alloy) helmets, purple tunics, greaves and shields out of the case.” [12] Xenophon, Anabasis, Book 1, II/16

This excerpt shows that the wearing of armour or even chest protection already seemed secondary. HANSON has shown that the full panoply was a burden that hoplites were reluctant to take on too early before combat [13] On the clutter of the complete hoplitic equipment: Davis HANSON, (1990), Le modèle occidental de la guerre, La bataille d’infanterie dans la Grèce Classique, translated from English by Alain Billault , Les belles lettres, collection Histoire, p87-99. These protections were less and less widespread in the classical period, period of the progressive disappearance of ritual warfare.

The “Greaves” are flexible bronze protections (1mm thick) from the ankle to above the knee. They fit perfectly to the morphology of the legs of their wearer and hold thanks to the elasticity of the metal that closes behind the calves. Although sometimes worn next to the skin, there must have been some models with internal padding. Here again, the study of the artefacts exhibited in the museum collections has enabled us to highlight the existence on certain models of fully pierced edges that allow the padding to be attached by sewing.

The “thorax”, especially worn in the archaic period, is a bronze armour (2 to 3mm) protecting the torso and having greatly evolved over time, going from a simple bell shape to works of art molding and imitating the musculature of the warrior. The front and back sides are hinged at the shoulders and attached with straps on the sides. Sometimes an addition covering the abdomen and lower abdomen is attached. This heavy armour weighs 15 to 20 kilos, it was therefore gradually replaced by lighter models made of leather, “Spolas”, or linen, “Linothorax”, which we will not describe here but which fulfils a similar function, the protection of the torso of the fighter. However, it is interesting to note that only the bronze “thorax” allows the warrior not to be compressed between the different ranks of his formation at the time of shock and phalanx thrust.

Conclusion

As we have seen, hoplite equipment varies from one fighter to another within the same phalanx. But three elements are recurrent and essential, a double hook shield to fit into the formation, a spear to fight, and a protection of the skull to be protected from the vast majority of adverse blows.

bibliography

- J.K. ANDERSON, Hoplitic Weapons and Offensive Arms , in Hoplites, the Classical Greek Battle Experience, V.D. Hanson, pp.15-37, London, Routledge, 1991.

- Walter DONLAN, James THOMPSON, The charge at Marathon: Herodotus 6.112, The classical Journal vol.71n No.4 PP.339-343, 1976.

- Pierre DUCREY, Guerre et guerriers dans la Grèce antique, Fribourg, office du livre, 1985.

- Michel FEUGERE, Helmets of Antiquity: Faces of the Mycenaean War in Late Antiquity, Paris, 1994.

- Victor Davis HANSON, Le modèle occidental de la guerre, La bataille d’infanterie dans la Grèce classique, Les belles lettres, collection Histoire, 1990.

- Jon Edward LENDON, Soldiers and Ghosts: Fighting in Antiquity, Editions Tallandier, Antiquity collection, 2009.

- Vincent TORRES, under the direction of Philippe JOCKEY (2015), “L’apport de l’expérimentation sur l’histoire du geste martial, cas d’étude appliquée : le déplacement au sein de la phalange dite hoplitique, approche expérimentale. “Dissertation 2 of history at the University of Aix-Marseille.

- Vincent TORRES, Hoplite, le premier guerrier de l’histoire, éditions Heimdal, Bayeux, 2018.

Primary sources

- Introduction of: HERODOTE [HERODOTUS], (1985), L’enquête (Histories), Livres I à IV, transl. Andrée Barguet, Gallimard collection Folio, Paris

- Introduction of: HERODOTE [HERODOTUS], (1985), L’enquête (Histories), Livres I à IV, transl. Andrée Barguet, Gallimard collection Folio, Paris

- XENOPHON, (1967) Œuvre Complète 2 : Anabase – Economique – Le banquet – De la chasse – La république des Lacédémoniens – La république des Athéniens (Complete Work 2 : Anabasis – Oeconomicus – Symposium – Cynegeticus – Constitution of the Lacedaemonians – Constitution of the Athenians), Transl. Pierre Chambry, Garnier-Flammarion

Notes & Références